Introduction

This is a tutorial for the Jujutsu version control system. It requires no previous experience with Git or any other version control system.

At the time of writing, most Jujutsu tutorials are targeted at experienced Git users, teaching them how to transfer their existing Git skills over to Jujutsu. This tutorial is my attempt to fill the void of beginner learning material for Jujutsu. If you are already experienced with Git, I recommend Steve Klabnik's tutorial instead of this one.

This tutorial requires you to work in the terminal. Don't worry, there's a chapter covering some terminal basics in case you're not 100% comfortable with that yet. The commands I tell you to run will often only work on Unix-like operating systems like Linux and Mac. If you're stuck on Windows, consider using WSL.

What is version control and why should you use it?

I will assume you're planning to use version control for software development, but it can be used for other things as well. For example, authoring professionally formatted documents with tools like Typst. The source of this tutorial is stored in version control too!

What these scenarios have in common is that a large body of work (mostly in the form of text) is slowly being expanded and improved over time. You don't want to lose any of it and you may want to compare or be able to go back to previous states of your work. Often, several people need to work on the project at the same time.

A general-purpose backup solution can keep a few copies of your files around. A graphical document editor can allow multiple people to edit the text simultaneously. But sometimes, you need a sharper knife. Jujutsu is the sharpest knife available.

Why Jujutsu instead of Git?

Git is by far the most commonly used VCS in the software development industry. So why not use that? Using the most popular thing has undeniable benefits. There is lots of learning material, lots of people can help you with problems, lots of other tools integrate with it etc. Why make life harder on yourself by using a lesser-known alternative?

Here's my elevator pitch:

-

Jujutsu is compatible with Git. You're not actually losing anything by using Jujutsu. You can work with it on any existing project that uses Git for version control without issues. Tools that integrate with Git mostly work just as well with Jujutsu.

-

Jujutsu is easier to learn than Git. (That is, assuming I did a decent job writing this tutorial.) Git is known for its complicated, unintuitive user experience. Jujutsu gives you all the functionality of Git with a lot less complexity. Experienced users of Git usually don't care about this, because they've paid the price of learning Git already. (I was one of these people once.) But you care!

-

Jujutsu is more powerful than Git. Despite the fact that it's easier to learn and more intuitive, it actually has loads of awesome capabilities for power users that completely leave Git in the dust. Don't worry, you don't have to use that power right away. But you can be confident that if your VCS-workflow becomes more demanding in the future, Jujutsu will have your back. This is not a watered-down "we have Git at home" for slow learners!

Learning Jujutsu instead of Git as your first VCS does have some downsides:

-

When talking about version control with peers, they will likely use Git-centric vocabulary. Jujutsu shares a lot of Git's concepts, but there are also differences. Translating between the two in conversation can add some mental overhead. (solution: convince your peers to use Jujutsu 😉)

-

Jujutsu is relatively new and doesn't cover 100% of the features of Git yet. When you do run into the rare problem where Jujutsu doesn't have an answer, you can always fall back to use Git directly, which works quite seamlessly. Still, having to use two tools instead of one is slightly annoying. I plan to teach such Git features in this tutorial in later levels. The tutorial should be a one-stop-shop for all Jujutsu users.

-

The command line interface of Jujutsu is not yet stable. That means in future versions of Jujutsu, some commands might work a little differently or be renamed. I personally don't think this should scare you away. Many people including me have used Jujutsu as a daily driver for a long time. Whenever something did change, my reaction was usually: "Great, that was one of the less-than-perfect parts of Jujutsu! Now it's even more intuitive than before!" Consider subscribing to GitHub releases of this tutorial. You will be notified if new versions of Jujutsu change something in a way that's relevant to what you learned in this tutorial.

Despite some downsides, I think the benefits are well worth it.

How to read this tutorial

Here's some information about how the tutorial is structured. Read carefully for the best experience.

Level up!

The tutorial is split into levels, which define the hierarchy in the sidebar. When you complete a level, you should probably put this tutorial away for a while and practice what you've learned. Once you're comfortable with those skills, come back for the next level.

There is one exception to this: If you're here because you need to collaborate with other people, you should complete the levels 1 and 2 right away.

Here's an overview of the available levels:

| Level | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | The bare minimum to get started. Enough for solo-projects like submitting homework as a student. |

| 2 | The bare minimum for collaboration, e.g. students doing a group project or software engineers working in a team. |

| 3 | Important problem-solving skills: undoing mistakes, resolving merge conflicts, restoring files from history. |

More levels are planned. The following chapter explains how to get notified about new content.

Reset your progress at any time

Throughout the tutorial, you will build an example repository. Later chapters depend on the state of previous ones. But don't be afraid to mess up or lose your progress by experimenting!

There is a script which automates the task of resetting your progress to the start of any chapter.

To identify the chapter you want to continue with, the script expects a keyword as an argument. Each chapter includes its precise reset command at the top, so you can easily copy-paste it. For example, the text box below contains instructions to reset your progress to the very beginning of the tutorial:

To reset your progress to the start of this chapter, run the following command:

curl https://jj-for-everyone.github.io/reset.sh | bash -s install

This method downloads the script from the internet and executes it right away. If you have security concerns about that, you can instead:

- Download the script here.

- Read the source to make sure it's safe. It's not doing anything complicated, it just executes the commands of the tutorial in sequence.

- Run the downloaded script (with the chapter-keyword as the first argument).

For convenience, the source of the script is also included in the expandable text box below.

Source of reset script

Source of reset script

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -euxo pipefail

red='\033[0;31m'

blue='\033[0;34m'

no_color='\033[0m' # No Color

error="${red}Error:${no_color}"

hint="${blue}Hint:${no_color}"

# The env variable JJ_TUTORIAL_DIR can be used to override the location of the

# tutorial repository. This is *intentionally not documented* in the tutorial,

# because doing so can lead to problems. For simplicity, the tutorial will

# continue to use the hardcoded path in code snippets to copy-paste into the

# terminal. If the location is changed, those code snippets will have to be

# adjusted manually. The feature is still there for opinionated folk who know

# what they're doing.

jj_tutorial_dir=${JJ_TUTORIAL_DIR:-$HOME/jj-tutorial}

if [ "${1:-x}" = "x" ] ; then

set +x

printf "$error Please provide the chapter keyword as the first argument.\n"

exit 1

fi

chapter="$1"

function success() {

set +x

echo "✅ Reset script completed successfully! ✅"

exit 0

}

rm -rf "$jj_tutorial_dir"

if [ "$chapter" = install ] ; then success ; fi

if ! command -v jj > /dev/null ; then

set +x

printf "$error Jujutsu doesn't seem to be installed.\n"

printf " Please install it and rerun the script.\n"

exit 1

fi

# make sure jj version is recent enough

detected_version="$(jj --version | cut -c 6-7)"

required_version="37"

if [ "$detected_version" -lt "$required_version" ] ; then

set +x

printf "$error Your Jujutsu version (0.$detected_version) is too outdated.\n"

printf " Please update to version 0.$required_version or later.\n"

printf "$hint If you installed Jujutsu with mise, as recommended in the installation\n"

printf " chapter, use the following commands to update:\n"

echo "

mise install-into jujutsu@latest /tmp/jj-install

mv /tmp/jj-install/jj ~/.local/bin

rm -rf /tmp/jj-install"

exit 1

fi

# Ensure existing user configuration does not affect script behavior.

export JJ_CONFIG=/dev/null

export GIT_CONFIG_GLOBAL=/dev/null

if [ "$chapter" = initialize ] ; then success ; fi

mkdir "$jj_tutorial_dir"

jj git init "$jj_tutorial_dir"/repo

cd "$jj_tutorial_dir"/repo

jj config set --repo user.name "Alice"

jj config set --repo user.email "alice@local"

jj metaedit --update-author

if [ "$chapter" = log ] ; then success ; fi

if [ "$chapter" = make_changes ] ; then success ; fi

echo "# jj-tutorial" > README.md

jj log -r 'none()' # trigger snapshot

if [ "$chapter" = commit ] ; then success ; fi

jj commit --message "Add readme with project title

It's common practice for software projects to include a file called

README.md in the root directory of their source code repository. As the

file extension indicates, the content is usually written in markdown,

where the title of the document is written on the first line with a

prefixed \`#\` symbol.

"

if [ "$chapter" = remote ] ; then success ; fi

git init --bare -b main "$jj_tutorial_dir"/remote

jj git remote add origin "$jj_tutorial_dir"/remote

jj bookmark create main --revision @-

jj bookmark track main

jj git push --bookmark main

if [ "$chapter" = update_bookmark ] ; then success ; fi

printf "\nThis is a toy repository for learning Jujutsu.\n" >> README.md

jj commit -m "Add project description to readme"

jj bookmark move main --to @-

jj git push

if [ "$chapter" = clone ] ; then success ; fi

cd ~

rm -rf "$jj_tutorial_dir"/repo

jj git clone "$jj_tutorial_dir"/remote "$jj_tutorial_dir"/repo

cd "$jj_tutorial_dir"/repo

jj config set --repo user.name "Alice"

jj config set --repo user.email "alice@local"

jj metaedit --update-author

if [ "$chapter" = github ] ; then success ; fi

if [ "$chapter" = branch ] ; then success ; fi

echo 'print("Hello, world!")' > hello.py

jj commit -m "Add Python script for greeting the world

Printing the text \"Hello, world!\" is a classic exercise in introductory

programming courses. It's easy to complete in basically any language and

makes students feel accomplished and curious for more at the same time."

jj git clone "$jj_tutorial_dir"/remote "$jj_tutorial_dir"/repo-bob

cd "$jj_tutorial_dir"/repo-bob

jj config set --repo user.name Bob

jj config set --repo user.email bob@local

jj metaedit --update-author

echo "# jj-tutorial

The file hello.py contains a script that greets the world.

It can be executed with the command 'python hello.py'.

Programming is fun!" > README.md

jj commit -m "Document hello.py in README.md

The file hello.py doesn't exist yet, because Alice is working on that.

Once our changes are combined, this documentation will be accurate."

jj bookmark move main --to @-

jj git push

cd "$jj_tutorial_dir"/repo

jj bookmark move main --to @-

jj git fetch

if [ "$chapter" = show ] ; then success ; fi

if [ "$chapter" = merge ] ; then success ; fi

jj new main@origin @-

jj commit -m "Merge code and documentation for hello-world"

jj bookmark move main --to @-

jj git push

if [ "$chapter" = ignore ] ; then success ; fi

cd "$jj_tutorial_dir"/repo-bob

tar czf submission_alice_bob.tar.gz README.md

echo "

## Submission

Run the following command to create the submission tarball:

~~~sh

tar czf submission_alice_bob.tar.gz [FILE...]

~~~" >> README.md

jj show > /dev/null

echo "*.tar.gz" > .gitignore

jj file untrack submission_alice_bob.tar.gz

jj commit -m "Add submission instructions"

if [ "$chapter" = rebase ] ; then success ; fi

jj bookmark move main --to @-

jj git fetch

jj rebase --onto main@origin

jj git push

if [ "$chapter" = more_bookmarks ] ; then success ; fi

cd "$jj_tutorial_dir"/repo

echo 'for (i = 0; i < 10; i = i + 1):

print("Hello, world!")' > hello.py

jj commit -m "WIP: Add for loop (need to fix syntax)"

jj git push --change @-

if [ "$chapter" = navigate ] ; then success ; fi

jj git fetch

jj new main

jj new 'description(substring:"Document hello.py in README.md")'

jj new main

if [ "$chapter" = undo ] ; then success ; fi

echo 'print("Hallo, Welt!")' >> hello.py

echo 'print("Bonjour, le monde!")' >> hello.py

jj commit -m "code improvements"

jj undo

jj commit -m "Print German and French greetings as well"

jj undo

jj undo

jj undo

jj redo

jj redo

jj redo

if [ "$chapter" = track ] ; then success ; fi

cd ~ # move out of the directory we're about to delete

rm -rf "$jj_tutorial_dir"/repo

jj git clone "$jj_tutorial_dir"/remote "$jj_tutorial_dir"/repo

cd "$jj_tutorial_dir"/repo

# roleplay as Alice

jj config set --repo user.name "Alice"

jj config set --repo user.email "alice@local"

jj metaedit --update-author

echo 'print("Hallo, Welt!")' >> hello.py

echo 'print("Bonjour, le monde!")' >> hello.py

jj commit -m "Print German and French greetings as well"

jj bookmark move main -t @-

jj git push

jj bookmark track 'push-*'

if [ "$chapter" = conflict ] ; then success ; fi

jj new 'description(substring:"WIP: Add for loop")'

echo 'for _ in range(10):

print("Hello, world!")' > hello.py

jj commit -m "Fix loop syntax"

jj new main @-

echo 'for _ in range(10):

print("Hello, world!")

print("Hallo, Welt!")

print("Bonjour, le monde!")' > hello.py

jj commit -m "Merge repetition and translation of greeting"

jj bookmark move main --to @-

jj git push

if [ "$chapter" = abandon ] ; then success ; fi

jj commit -m "Experiment: Migrate to shiny new framework"

jj git push --change @-

jj new main

jj commit -m "Experiment: Improve scalability using microservices"

jj git push --change @-

jj new main

jj commit -m "Experiment: Apply SOLID design patterns"

jj git push --change @-

jj new main

jj abandon 'description(substring:"Experiment")'

jj git push --deleted

if [ "$chapter" = restore ] ; then success ; fi

rm README.md

jj show &> /dev/null

jj restore README.md

jj restore --from 'description(substring:"Fix loop syntax")' hello.py

jj commit -m "Remove translations"

jj bookmark move main --to @-

jj git push

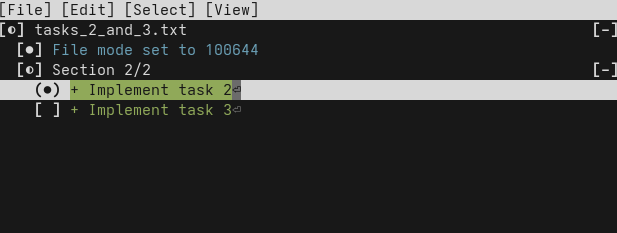

if [ "$chapter" = commit_interactive ] ; then success ; fi

# `jj commit --interactive doesn't work in a script, so we reproduce the same

# commits a little differently.

echo "Implement task 1" > task_1.txt

jj commit --message "Implement task 1" task_1.txt

echo "Implement task 2" > tasks_2_and_3.txt

jj commit --message "Implement task 2"

echo "Implement task 3" >> tasks_2_and_3.txt

jj commit --message "Implement task 3"

jj bookmark move main --to @-

jj git push

if [ "$chapter" = complete ] ; then success ; fi

set +x

echo "Error: Didn't recognize the chapter keyword: '$chapter'."

exit 1

Stay up to date

Both this tutorial and Jujutsu are still evolving. In order to keep your Jujutsu knowledge up-to-date, subscribe to releases of the tutorial's GitHub repo. You'll get an email from GitHub whenever I post a release, which basically allows me to send you notifications.

I'm planning to post releases for two reasons in particular:

- I finished writing a new level.

- A new version of Jujutsu includes changes that are relevant to readers of this tutorial.

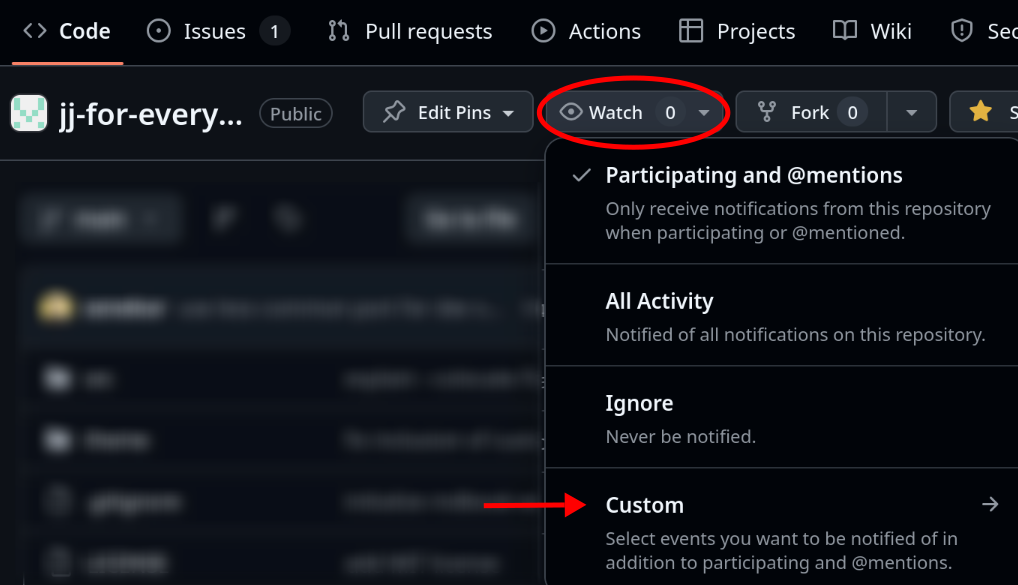

To subscribe: Visit the GitHub repo, click on "Watch", then "Custom" and lastly select "Releases".

The following levels are planned for the future:

| Level | Description |

|---|---|

| 4 | History rewriting skills. These will allow you to iterate toward a polished version history, which pays dividends long-term. Some projects require you to have these skills in order to meet their quality standards. |

| 5 | Productivity boosters, advanced workflows, lesser-known CLI functions and a little VCS theory. Completing this level means you have mastered Jujutsu. |

| 6 | Additional topics that only come up in specific situations: tags, submodules, workspaces etc. Consider skimming the list of topics and come back once you have an actual need for it. |

I consider the tutorial up-to-date with Jujutsu version 0.37, which was released in January 2026. If that's more than a couple months in the past, I probably stopped updating this tutorial.

Help make this tutorial better

If you find a typo, you can suggest a fix directly by clicking on the "edit" icon in the top-right corner. If you have general suggestions for improvement, please open an issue. I am also very interested in experience reports, for example:

- Do you have any frustrations with Jujutsu which the tutorial did not help you overcome?

- Was there a section that wasn't explained clearly? (If you didn't understand something, it's probably the tutorial's fault, not yours!)

- Did you complete a level but didn't feel like you had the skills that were promised in the level overview?

- Is there something missing that's not being taught but should?

- Do you feel like the content could be structured better?

Thank you for helping me improve this tutorial!

Terminal basics

This chapter is not about Jujutsu or even version control. But the tutorial requires you to work in the terminal, so let's cover the basics. If you're already comfortable in the terminal, you can confidently skip this chapter.

There are a lot of small things to cover, so here's a little table of contents:

- What is the terminal?

- The prompt

- Entering commands

- The current working directory

- Copy-pasting commands

- Redirection

- Pagers

- Variables and the environment

- The

PATHvariable - Startup scripts

What is the terminal?

The terminal is an application that lets you enter commands to the operating system in the form of text. The commands usually produce text themselves, which will be displayed to you.

The terminal used to be the primary way people interact with a computer. That was before the time of graphical user interfaces. Today, the terminal works much the same as it did in the past, but it's inside a normal app window now. The app can have different names, but "Terminal" and "Console" or variations thereof are most common.

The prompt

When you start the terminal, the initial text you will see is called the prompt. Whenever a command finishes running, the prompt will be shown again. That's your sign that you can start entering your next command. Here's an example of what a prompt can look like:

[username@hostname ~]$

This shows some information that'll be useful later, but don't worry about it for now.

The prompt usually ends with a dollar $ or percent % sign, so you can easily recognize it.

The dollar sign is often used as a short representation of the prompt.

Entering commands

Being presented with the prompt is our cue to execute commands, so let's do that. Type the following and then press Enter:

echo Hello, terminal!

The terminal will split your commands into words based on whitespace. The above command has three words:

echoHello,terminal!

The first word is the program to run.

The terminal will find a program called echo on your computer and run it with the two arguments Hello, and terminal!.

The program is free to interpret these arguments however it wants.

The program called echo happens to simply print its arguments back to the terminal:

$ echo Hello, terminal!

Hello, terminal!

The current working directory

One fundamental concept of the terminal is the current working directory. It's a location in your filesystem, the one "where you currently are".

Most commands you run behave differently based on this "current location".

Because of that, we need to be able to change it.

The command to do that is called cd, short for "change directory".

You probably have a folder called "Downloads", but you can substitute a different one in this example:

[username@hostname ~]$ cd Downloads

[username@hostname Downloads]$

Oh! Did you notice that the prompt changed? The current working directory, or CWD for short, is so important that it's usually shown somewhere in the prompt. That way you always know "where you are".

Before running cd in the example above, the CWD was apparently the tilde ~ character.

That's a shorthand for your user's home directory.

On Linux, that's /home/username.

Another way to determine your CWD is to call the command pwd, short for "print working directory".

It expands the shorthand tilde ~ character to its full path.

[username@hostname Downloads]$ pwd

/home/username/Downloads

[username@hostname Downloads]$

One example of a CWD-aware command is ls, which lists files and directories.

Go ahead and run ls in your Downloads folder.

Maybe it's time to clean it up a little...?

The important lesson to take away here is: Be aware of your current working directory. If a command doesn't do what you want, you might just be in the wrong place.

Copy-pasting commands

This tutorial contains many code blocks that contain commands for you to copy-paste into your terminal. Multiple commands can be on separate lines and you can copy-paste them all at once without issues. If you hover your mouse over the top-right corner of a code block, a hidden copy-button will appear. Very useful!

For historical reasons, Ctrl+C and Ctrl+V don't do copy and paste in the terminal. Instead, you need to use Ctrl+Shift+C/V respectively. If you're using a Mac, Command+C/V works normally.

If you forget about this and type Ctrl+V without Shift in an attempt to paste a command into the terminal, it will actually get messed up a little. You can't just try again with Ctrl+Shift+V. You would end up with something like this:

$ ^[[200~echo Hello, terminal!~

These weird characters are an "escape sequence" caused by typing Ctrl+V without Shift. This command will not work. So, if you make the mistake of forgetting Shift, just hit Enter a couple of times until you get a fresh prompt, then try again.

Some of the commands will contain comments, which are lines of text following a pound # character.

The terminal simply ignores them.

They are used to make commands more understandable to human readers, but they don't affect the command execution.

You can practice by copy-pasting the following command into your terminal:

# Here are some example comments:

#

# This is the program being run.

# |

# | This is the start of the first argument.

# | |

# | | This is the start of the second argument.

# v v v

echo Hello, terminal! # Placing a comment next to a command is also allowed.

Redirection

We've seen how the echo command prints its arguments back to the terminal.

But that's just the default.

echo just prints to something called "standard out", or "stdout".

That is usually connected to your terminal.

But you can also redirect the stdout of a program, for example to a file with the > operator.

An example looks like this:

echo "bread, onions, tea" > groceries.txt

If you run this command, it will create a file called "groceries.txt" in your CWD.

The content of the file will be "bread, onions, tea".

If a file with the same name already existed, it will be overwritten.

In addition to the > operator, there is also the >> operator.

It appends text to the end of a file, instead of overwriting it.

In this book, I will often tell you to manipulate a file by running a command that looks like the one above.

Pagers

Some commands you run in the terminal print a lot of text. It can be tedious to scroll all the way back up to the point where the command output started. This is where a pager can help. It takes the output from another program and shows it to you from the beginning.

Some programs will display their output in a pager automatically, because they know they will be printing a lot of text. Jujutsu also does that sometimes. Given that you may "accidentally" end up in a pager, you need to know that you can exit a pager by typing q!

If the output of Jujutsu is displayed in a pager, the bottom left corner will be a colon : character and your prompt won't be shown.

One way you can experiment with using a pager is by running man tar, which opens the manual page for the tar command.

Various key bindings let you navigate in the pager. The arrow keys, "page up" and "page down" all work as expected. Another super useful one is this: Typing / allows you to enter a search term, then Enter starts the search. Step through the search hits with (lowercase) n and step backwards with (uppercase) N.

Variables and the environment

Running programs on your computer by typing their name is only scratching the surface of what the terminal can do.

It actually has a whole little programming / scripting language built-in.

For example, you can store values in variables with the equal = sign and evaluate them with the dollar $ sign:

$ my_name=Alice

$ echo Hello, $my_name!

Hello, Alice!

Normal variables like above cannot be read by programs you run. They are only for your own use in the current terminal session. However, variables can be exported into the environment, which makes them accessible for programs to read. This is an alternative way to tell programs what you want them to do. The more common way is with arguments on the command line, but exported variables are useful in some situations.

You can export a variable separately from setting its value or do it all in one line:

MY_NAME=Alice

export MY_NAME

export MY_NAME=Alice

Such exported variables are usually referred to as environment variables. They are not required to be uppercase, but it's a strong convention. It makes it easy to know which variables can be read by other programs.

The PATH variable

One environment variable that can be difficult to understand at first is the PATH variable.

First, let's print it to see what it contains:

$ echo $PATH

/home/username/.local/bin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin

Your output may well look different, but the structure is the same:

It's a list of filesystem paths separated by the colon : character.

In this case, there are three paths:

/home/username/.local/bin/usr/local/bin/usr/bin

What do these three paths mean?

They are the places where your terminal searches for programs to run!

Let's mess with it to see what happens.

Set the PATH variable to the empty string:

export PATH=""

Now try to run a program, like ls for example:

$ ls

bash: ls: No such file or directory

Oops.

Setting the PATH variable to the empty string tells the terminal to not search for programs anywhere.

Therefore, the programs ls cannot be found anymore.

We could fix this by copy-pasting the previous value of PATH and export that again.

But if you mess up the value of an environment variable for real, you often don't know what the previous, correct value was.

So it's easiest to just close the terminal window and open a new one.

All variables will be reset to their default.

So, if modifying the PATH variable can break your session, should you just never touch it?

Not quite.

Sometimes you want (or need) to install programs in a different location than where your terminal searches for them by default.

In that case, you need to extend the list of paths stored in the PATH variable.

Here's an example:

export PATH="/home/username/my-local-programs:$PATH"

This starts with a new path at the front of the list, then there's the colon : separator and lastly the rest of the list, which is the previous value stored in PATH.

Startup scripts

The above command to edit the PATH variable will only affect the current terminal session.

So, if you close the terminal and reopen a new window, the value of PATH will be reset to its default.

But that may not be desirable.

If you install programs into a custom location, you may want all your future terminal sessions to find those programs automatically.

That's where startup scripts come into play. They are files containing a list of commands (also known as scripts). Startup scripts are automatically executed whenever you open a new terminal, before you can even type the first command. So that's the perfect place to make permanent changes to all your future terminal sessions!

The location and name of your startup script depend on your shell, i.e. your specific "flavor" of terminal.

The terminal is pretty standardized, so we mostly don't need to worry about different shells.

This is an exception.

If you're using Linux, your shell is probably called bash.

If you're using Mac, your shell is probably called zsh.

To find out for sure, you can read the SHELL environment variable:

$ echo $SHELL

/bin/bash

If your shell is bash, you should add your custom startup commands to the file ~/.bashrc.

In the case of zsh, the startup script is ~/.zshrc.

For now, print the content of your startup script. It's probably complicated, so don't try to understand it all. Nevertheless, taking a look is a great way to get acquainted with the terminal:

# for bash

cat ~/.bashrc

# for zsh

cat ~/.zshrc

If most of this stuff was news to you, pat yourself on the back! You've already learned a lot. This should be enough knowledge about the terminal to get you through the tutorial.

Don't hesitate to come back here and revise from time to time. The rules of the terminal are not the most intuitive, so it can take a couple attempts for them to settle in.

Level 1

This level will provide you with the bare minimum of skills you need to get work done. It's only enough for the simplest use cases and you're working on your own. For example, students who track and submit their homework with a Git repository won't need more than this.

The following "cheat sheet" contains the most important commands from level 1. Use it to prime your brain before getting started and remind yourself later when you forget something.

Configure your authorship information

jj config set --user user.name "Alice"

jj config set --user user.email "alice@local"

Initialize a repository

jj git init <DESTINATION>

Clone an existing repository

jj git clone <PATH_OR_URL> <DESTINATION>

Commit the changes you made

jj commit

Push your latest commit to the "main" bookmark

jj bookmark move main --to @-

jj git push

Installation and setup

There are many ways to install Jujutsu and the best one depends on your system. If you don't care at all about how Jujutsu is installed, you can copy-paste these commands:

curl https://mise.run | sh

~/.local/bin/mise install-into jujutsu@latest /tmp/jj-install

mv /tmp/jj-install/jj ~/.local/bin

rm -rf /tmp/jj-install

exec $SHELL --login

Now run jj --version to verify the installation.

It should print the currently installed version of Jujutsu, something like jj 0.36.0-blabla.

If the output is an error instead, e.g. bash: jj: command not found..., open the text box below.

jj: command not found...

jj: command not found...

Your system probably doesn't add the installation directory ~/.local/bin to the PATH environment variable.

To fix that, you first need to figure out what shell you're using:

echo $SHELL

The output should end with either "bash", or "zsh".

That's your shell.

Next, put a command adding ~/.local/bin to your PATH variable into your shell's startup script:

# for bash:

echo 'export PATH=$HOME/.local/bin:$PATH' >> ~/.bashrc

# for zsh:

echo 'export PATH=$HOME/.local/bin:$PATH' >> ~/.zshrc

Lastly, close the terminal and open a new one so the changes take effect.

Explanation of installation commands

Explanation of installation commands

Installing software is more difficult than one might think.

It depends on many factors like CPU architecture and operating system.

That's why there's not a single, easy command we can run to install Jujutsu on any system.

Instead, we first install another program that specializes in installing software called mise.

(You can read more about mise on its website.)

The first command curl https://mise.run | sh downloads and runs a script from the internet that installs mise for you.

This is kind of dangerous and you should be careful when executing scripts from the internet.

People could place malicious commands in the script you're downloading.

But it's a convenient technique if you trust the owner of the website you're loading the script from.

The second command runs mise to download Jujutsu into a temporary directory.

We have to specify the full path to the mise binary (~/.local/bin/mise), because at this point we don't know if ~/.local/bin is included in your PATH variable.

(See the "Terminal basics" chapter for an explanation of that.)

mise takes care of downloading the right binary for your operating system and CPU architecture.

The following command moves the downloaded binary to ~/.local/bin, which is the customary place for user-local programs.

rm -rf /tmp/jj-install ("remove recursive force") deletes the temporary download directory and its content.

Lastly, exec $SHELL --login restarts your shell, which causes its startup scripts to run again.

Some Linux distributions like Ubuntu only add ~/.local/bin to the PATH variable if that directory exists when the terminal is started.

So, restarting the terminal after installing Jujutsu is a simple way to make sure the system will find the new program.

Maybe there are distributions which don't add ~/.local/bin to PATH at all, which would mean those commands don't work on such a system.

I'm not aware of such distributions.

(Please open an issue if you know of a relevant one!)

You can fix such an issue for yourself by extending the PATH variable in your shell startup script.

Other installation methods

Other installation methods

The official installation instructions for several different platforms are here. I will mention a few methods that I consider important as well.

If you use cargo-binstall, this works great:

cargo-binstall jj-cli

If you're a Mac & Homebrew user, this one's for you:

brew install jj

If you have the Rust toolchain installed and would like to compile from source, you can run:

cargo install --locked --bin jj jj-cli

You can also download a binary directly from Jujutsu's release page. Scroll down to "Assets", there is a list of archives to download. The right one depends on two things: your operating system and your CPU architecture. Look for the strings matching your system in the names of the archives.

How to identify your operating system:

| operating system | string to look for |

|---|---|

| Linux | unknown-linux-musl |

| Mac | apple-darwin |

| Windows | pc-windows-msvc |

How to identify your CPU architecture:

| CPU brand | string to look for |

|---|---|

| Intel | x86_64 |

| AMD | x86_64 |

| Apple | aarch64 |

| ARM | aarch64 |

| Qualcom (Snapdragon) | aarch64 |

Once you have downloaded the right archive, you need to extract it.

You should be able to right-click on the downloaded archive in your file explorer and select "extract" or something similar in the drop-down.

The extracted folder will contain documentation and a file called "jj".

You need to move that into the directory ~/.local/bin/.

(Or another location where you keep your programs if you know what you're doing.)

Initial configuration

Jujutsu is very configurable, but we don't care about most knobs and dials right now. The only thing that you must configure is your name and email. This is required metadata and some things won't work right without this information. However, you don't have to enter your real name and email, in case you're not comfortable storing that information in the repositories you're planning to work on.

If you're working on school or work projects, it's probably fine to configure your real name and school / work email. These repositories are usually not publicly accessible.

If you're planning to work on open source projects that anyone can see, you may want to be more careful. You could use your GitHub handle as username, but many are comfortable using their real name too. The email address is more important. If you use your normal, private email address, there is a risk of receiving undesirable emails at that address. You might consider using a dedicated address just for open source work. Another alternative is to use an address provided by GitHub. It identifies your GitHub account, but you cannot receive emails through it. Go to GitHub's email settings and select "Keep my email address private", your private email address will then be shown at the top.

Here are the commands to configure your username and email:

jj config set --user user.name "Anonymous"

jj config set --user user.email "anon@local"

If you want shell completions, follow the instructions here. If you don't know what a "shell completion" is, don't worry, it's not important.

Installing a simple text editor

Jujutsu will sometimes ask you to edit a text file.

The default text editor used for that purpose is nano on Linux and Mac.

It works fine, but it can be counter-intuitive for new users.

(Ctrl+O is saving the file and Ctrl+X is closing the program.)

This is optional, but I recommend you install a text editor called edit.

I consider it to be the simplest and most intuitive alternative.

If you installed Jujutsu with mise (as suggested above) you can also install edit the same way:

mise install-into edit@latest /tmp/edit-install

mv /tmp/edit-install/edit ~/.local/bin

rm -rf /tmp/edit-install

If you installed Jujutsu using another method, you'll want to install edit on your own as well.

Next, we need to configure Jujutsu to use edit when opening a text file:

jj config set --user ui.editor edit

From now on, when Jujutsu opens a text file for you, it will do so using edit.

When you're done editing a file, click on "File", then "Exit", in the menu bar or press Ctrl+Q to exit the text editor.

It will ask you if you want to save the file, which you confirm by pressing Enter.

That's it!

I will remind you how it works the first time we need it.

Initializing a repository

Reset your progress

Reset your progress

To reset your progress to the start of this chapter, run the following command:

curl https://jj-for-everyone.github.io/reset.sh | bash -s initialize

A "repository" is a directory (folder) where Jujutsu keeps track of all files, including the ones in subdirectories.

A repository usually corresponds to a project, so the version history of unrelated projects are not tied to each other.

In this tutorial, we'll use ~/jj-tutorial/repo as the location of our repository.

Don't put it somewhere else, otherwise some commands I tell you to run won't work later.

(If you don't like the clutter in your home directory, you can always delete it and use the reset script when you continue with the tutorial.)

The command to initialize a new repository is jj git init <DESTINATION>.

We use cd to change our working directory to the new repository.

Copy-paste these commands into your terminal:

mkdir ~/jj-tutorial

jj git init ~/jj-tutorial/repo

cd ~/jj-tutorial/repo

Let's examine our first jj command.

git is the subcommand responsible for various Git-specific compatibility features.

One of them is the init command, which initializes a new repository that's compatible with Git.

What does "initializing a repository" mean?

Essentially, Jujutsu creates two directories .git and .jj.

These contain all information about the version history.

Why two directories?

The .git directory contains all the important stuff, stored in a way that is compatible with Git.

The .jj directory contains additional metadata which enable some of Jujutsu's advanced features.

You should never manipulate files in these directories directly! Their content is a well-structured database. If you corrupt the database format, the repository might become broken. We'll talk about a second layer of backup in the chapter about remotes.

Files and directories starting with a dot are hidden by default, but you can verify they were created with ls -a:

$ ls -a

.git .jj

In the previous chapter, you configured Jujutsu with your name and email address. This configuration applies to all of your repositories by default. However, for our example repository, we'll actually pretend to be "Alice", who is later joined by "Bob" to simulate collaboration. The below commands perform the author configuration only for this specific repo. There's no need to memorize these commands, they are normally not needed.

# applies configuration to a single repository only

# vvvvvv

jj config set --repo user.name "Alice"

jj config set --repo user.email "alice@local"

# reset already recorded global authorship information:

jj metaedit --update-author

Inspecting the state of a repository

Reset your progress

Reset your progress

To reset your progress to the start of this chapter, run the following command:

curl https://jj-for-everyone.github.io/reset.sh | bash -s log

cd ~/jj-tutorial/repo

So, now we've got an empty repository.

Let's take a closer look at it.

The command jj log shows you a visual representation of your version history.

If you run it, you should see something like this:

@ mkmqlnox alice@local 2025-07-22 20:15:56 f6feaadf │ (empty) (no description set) ◆ zzzzzzzz root() 00000000

There's a lot going on already, so let's unpack it one-by-one.

In the leftmost column, there's an @, a line and a diamond.

The @ sign represents the present state of the files in the repository, also known as the "working copy".

The diamond indicates an earlier state and the line connecting them means one state descends from another.

Older states are at the bottom and more recent ones are at the top.

In this case, the diamond is the "root", an empty state from which all others descend.

It always exists and cannot be modified.

Allow me to introduce a little bit of VCS-lingo.

Until now, I've used the word "state" to refer to the "working copy" (@ sign) and the "root" (diamond).

These states are snapshots of your repository, storing all files in the repo and their content.

The technical term for these snapshots is commit.

The commit is the most important data structure in the repository and I will use that term from now on.

So what's going on to the right of the first column? That's all important metadata about your commits. Let's look at the one of the working copy commit:

mkmqlnox alice@local 2025-07-22 20:15:56 f6feaadf (empty) (no description set)

The first word is mkmqlnox, a random-looking identification number called the change ID.

Next is the email address you previously configured, indicating that you are the author of this commit.

After that is a timestamp, indicating when the commit was created.

Last on the first line is another random looking word f6feaadf.

It's also an identification number, but this one is called the commit hash or commit ID.

The change ID is more important than the commit hash, which is reflected in their position in the log output: the important one comes first.

We'll discuss the purpose of these IDs in more detail later.

Note that in the example output I provide in this tutorial, the change IDs and timestamps are not always consistent. While writing the tutorial, I go back and forth, changing stuff and recreating my example repository. This causes change IDs and timestamps to change.

On the second line, the word "(empty)" indicates that none of the files in this commit were changed compared to the previous commit. Lastly, "(no description set)" is self-explanatory and foreshadows the possibility of giving descriptions to commits.

Even though the repository is empty at this point, we already get a decent understanding of what a repository is. It consist of a set of commits which are related to each other, where one commit is said to be the parent or the child of another. These commits store snapshots of the state of your files, as well as relevant metadata like authorship, timestamp and description.

Getting help about using Jujutsu

We've now used two of Jujutsu's commands: jj git init and jj log.

There are a lot of commands and flags to modify their behavior.

I will introduce everything you need, but sometimes you may need to refresh your mind.

It can also just be valuable to explore on your own.

You can pass the --help flag to any command to view contextual documentation.

For example, jj --help will show you the full list of top-level commands that Jujutsu supports.

jj log --help will show you specific information about how to use the log command, i.e. how to modify its behavior according to your needs.

These help pages will feel overwhelming at first. But something always sticks, even if you don't notice at first. If you keep coming back, you will soon become very efficient at finding relevant information this way.

Making changes

Reset your progress

Reset your progress

To reset your progress to the start of this chapter, run the following command:

curl https://jj-for-everyone.github.io/reset.sh | bash -s make_changes

cd ~/jj-tutorial/repo

Your primary goal is always to work on a project, Jujutsu just helps you manage your work. So let's pretend we're doing some actual work by putting stuff in a file:

echo "# jj-tutorial" > README.md

When you change files in a directory tracked by Jujutsu, what you're conceptually doing is modifying the working copy commit.

Let's see what jj log has to say now:

@ mkmqlnox alice@local 2025-07-22 20:19:25 e21958c2 │ (no description set) ◆ zzzzzzzz root() 00000000

A couple of things have changed:

- The timestamp of the commit was updated.

- The commit hash changed. That's one of the reasons the commit hash is less interesting, it changes every time anything else in the commit changes.

- The commit is not "(empty)" anymore!

The last point means that our new file was successfully recorded in the working copy commit.

Creating a new commit

Reset your progress

Reset your progress

To reset your progress to the start of this chapter, run the following command:

curl https://jj-for-everyone.github.io/reset.sh | bash -s commit

cd ~/jj-tutorial/repo

Once we are done with a set of changes, we should create a new commit. If we don't do that, the next changes we make will be recorded into the same commit as the previous ones. That would make it harder to understand the evolution of a project later.

Before we create a new commit, we also need to give a description to the one we've been working on so far. Every commit needs to have a description, even if it's a short one.

So, there are conceptually two things we need to do now:

- Give a description to the changes we just finished making, the ones that were recorded in the existing working-copy (

@) commit. - Start working on a completely new commit, which is the child of the one we just finished.

A source of confusion if you know Git

A source of confusion if you know Git

This tutorial assumes that you have no experience with Git.

However, if you have used Git before, it might actually be more difficult for you to understand this.

The reason is that both Git and Jujutsu have a subcommand called commit, but they work differently.

In Git, changes you make are not recorded automatically into commits.

Instead, they exist outside of any commit, until you add them to one manually.

The command git commit creates a commit containing the new changes as well as the new commit message.

In Jujutsu, there is always a commit already and any changes you make are automatically recorded into it.

So, the description you type during jj commit will be applied to a commit that has already existed for some time.

The new commit that's being created is completely empty and has no description.

It's ready for auto-recording of the upcoming changes you will be making.

The command to complete both of these tasks at once is:

jj commit

This will open a text editor so you can write a description for the commit.

If you followed my instructions during installation and setup, the text editor will be edit.

When you're done writing the description, click on "File", then "Exit", in the menu bar or press Ctrl+Q to exit the text editor.

Confirm that you want to save the file by pressing Enter.

You may notice that the text file doesn't start empty. It already contains a few lines:

JJ: This commit contains the following changes:

JJ: A README.md

JJ:

JJ: Lines starting with "JJ:" (like this one) will be removed.

These lines starting with JJ: are comments, similar to lines starting with a pound # in the terminal.

They will not be part of the final commit description, so you don't need to delete them.

Jujutsu uses these comments to remind you which files you modified when working on this commit.

That can be helpful inspiration for a good commit description.

Here's an example description you could type (or copy-paste) into the text editor:

Add readme with project title

It's common practice for software projects to include a file called

README.md in the root directory of their source code repository. As the

file extension indicates, the content is usually written in markdown,

where the title of the document is written on the first line with a

prefixed `#` symbol.

There is a little bit of structure here that you should follow. The first line of the description is called the subject. Sometimes the subject line is all you need, but to describe your changes in more detail, you can follow it up with a body. Subject and body are separated by an empty line. Both of them should not exceed 72 characters per line.

Commit messages are important, because they make it easier for you and others to understand the changes and their motivation later on. This importance lies on a spectrum: The more people work on a project and the longer-lived it is, the more important good commit messages become. For example, the Linux kernel is a multi-decade project with thousands of people working on it together. Linux developers put a lot of thought and effort into good commit messages. On the other extreme of the spectrum may be a student's repository for storing the homework of a single lecture. The project is over within a couple of months and there is little chance of the student ever digging into the history, let alone anyone else. That student probably won't invest much time into good commit messages.

More tips for good commit messages

More tips for good commit messages

Here are some additional conventions that are good practice for any type of project.

Try to keep the subject line below 50 characters

While 72 characters is the hard limit, the subject line usually benefits from being as concise as possible.

It is shown in many places where space is scarce and people want to get a general idea of your changes without reading too much.

If you find yourself exceeding 50 characters regularly, you may be combining multiple unrelated changes into a single commit.

If you put unrelated changes into separate commits, finding concise subject lines becomes easier.

However, there are often situations where 50 characters is just too restrictive, so don't worry about going above when necessary.

Use imperative mood in the subject line

A common instinct when writing commit messages it to describe what you did in the past tense, e.g. "Fixed bugs and improved code".

Another one is to describe the content of the commit, e.g. "bug fixes and code improvements".

Instead, write the subject line as if giving a command or instruction, e.g. "Fix bugs and improve code".

A simple rule of thumb is that the subject should complete the sentence "If applied, this commit will...".

The resulting history will be more natural to read.

Note that this primarily applies to the subject, the style of the body can be more flexible.

Put yourself in the shoes of the reader

The target audience for your commit messages are future readers of the project history.

They are trying to understand what your changes did and why.

They can always read the content changes directly for how they did that, so the ideal commit message should complement that.

Great candidates include information that's not present in the content itself as well as guidance to understand the changes more quickly.

Let's see the result of running jj commit with jj log:

@ pwpuwyto alice@local 2025-07-22 20:22:36 35de496a │ (empty) (no description set) ○ mkmqlnox alice@local 2025-07-22 20:20:34 5b79353a │ Add readme with project title ◆ zzzzzzzz root() 00000000

There are a few things to observe here:

- The new commit is a child of our previous working copy commit.

- The previous commit shows the subject line of the description we gave it.

- The new commit became our working copy, meaning any further file changes will be recorded into the new commit. This marker is not important and you can ignore it.

- The previous commit has a different symbol (circle

○) than the root commit (diamond◆). This is related to an important feature, which we'll learn about later.

We now have the tools for the most basic version control workflow:

- make some changes

- create a new commit

Repeating these two steps is what you'll do the most, when working on a version-controlled project.

Sending commits to a remote

Reset your progress

Reset your progress

To reset your progress to the start of this chapter, run the following command:

curl https://jj-for-everyone.github.io/reset.sh | bash -s remote

cd ~/jj-tutorial/repo

We now have a commit which we don't want to lose.

The way we're using Jujutsu right now, we don't have a backup at all.

What would happen if we delete the ~/jj-tutorial/repo directory on disk?

The .git and .jj subdirectories would be deleted as well.

Since our entire version control database is stored in there, we wouldn't be able to recover any of our work!

We can fix that by duplicating our commit at another location, a so-called remote. Besides providing a backup, sending commits to a remote also allows you to share your work more easily for collaboration.

The most popular form of a remote is to host a repository with an online service like GitHub. That requires an account and a little setup though, so we'll use a simpler approach in this tutorial. Your remote will be stored in a new directory on your computer, at a different location than your primary repository. That style of remote is bad as a backup and bad for collaboration, but it's perfect for learning how remotes work. There are a few practical tips about using GitHub in a later chapter.

Initializing the remote

The following command will initialize a new repository for use as a remote:

git init --bare -b main ~/jj-tutorial/remote

Since you will likely use a different style of remote for real projects, you don't need to understand the details here. If you're curious anyway, expand the text box below.

The difference between remote (bare) and regular repositories

The difference between remote (bare) and regular repositories

git init --bare is very similar to jj git init, which we used to create our main repository.

However, instead of a "regular" Jujutsu repository, it creates a "bare" Git repository.

What's the difference?

Think of a regular Jujutsu repository as consisting of two parts: (1) Jujutsu's internal database stored in the .git and .jj directories and (2) all the actual files of your project, which you can modify - your working copy.

The term "copy" is key here, because all the files are also stored in the internal database.

The only reason a copy of the files exists outside the database is so you can read and modify them - "work" with them.

So, "working copy" is a fitting name indeed.

A bare repository is a Git repository without a working copy and without any Jujutsu-specific metadata.

Since we will only use the bare repository for sending and receiving commits, we don't need a working copy or the .jj directory.

If you inspect the content of the new bare repository, it will look very similar in structure to the content of the .git directory in our main repository:

ls -lah ~/jj-tutorial/repo/.git

ls -lah ~/jj-tutorial/remote

The -b main part ensures the default branch is called "main".

If unspecified, the default branch can be different based on installation, configuration, etc.

This would cause problems later.

Connecting to a remote

A repository is connected to a remote by storing its location under a specific name. Remotes can be called anything, but when there is only one, the convention is to call it origin:

jj git remote add origin ~/jj-tutorial/remote

Here we connect to the remote by specifying its path on our filesystem.

When using a repository hosted on GitHub or similar services, the path is replaced with a URL.

More on that later.

If everything went well, origin should now appear in the list of remotes:

jj git remote list

Adding a bookmark

There is another speed bump before we can send our work to the remote. Remote repositories can receive a lot of commits, not all of which end up being needed in the long run. Therefore, it's desirable that commits which aren't needed anymore can be deleted automatically. How does the remote know which commits to delete and which to keep? With bookmarks!

A bookmark is a simple named label that's attached to a commit. Every commit with such a bookmark label is considered important and won't be deleted automatically. Because of that mechanism, a bookmark is required for sending commits to a remote.

Let's create a bookmark called main and point it to our completed commit. The name "main" is a convention that represents the primary state of the project. In legacy projects, the name "master" is also still in widespread use.

jj bookmark create main --revision mkmqlnox # <- substitute your change ID here

The command jj bookmark create expects a name (main) and a commit to which the bookmark should point.

We identify the commit by its change ID (--revision mkmqlnox).

For our purposes, the word "revision" is a synonym for "commit".

The flag --revision can also be abbreviated as -r.

Let's check the result with jj log:

@ pwpuwyto alice@local 2025-07-22 20:22:36 35de496a │ (empty) (no description set) ○ mkmqlnox alice@local 2025-07-22 20:20:34 main 5b79353a │ Add readme with project title ◆ zzzzzzzz root() 00000000

Great!

We can see that the bookmark main is correctly pointing to our recently completed commit.

Tracking a bookmark

We are now learning about bookmark, because we want to send commits to a remote. However, bookmarks can also be used for local-only purposes. For example, you can more easily refer to a commit by making a bookmark with a memorable name point to it. So, you may not want to send all of your bookmarks to a remote.

Jujutsu identifies bookmarks which are supposed to be sent to a remote with a "tracking" state.

In order to send the main bookmark to our remote, we need to "track it" first:

jj bookmark track main

Pushing the bookmark

Now that we're connected and have a bookmark, let's finally send our commit to the remote. The technical term for sending commits is "pushing" them. You will often hear phrases like "pushing to the remote" or "pushing to GitHub". The command for pushing a specific bookmark is:

jj git push --bookmark main

Updating bookmarks

Reset your progress

Reset your progress

To reset your progress to the start of this chapter, run the following command:

curl https://jj-for-everyone.github.io/reset.sh | bash -s update_bookmark

cd ~/jj-tutorial/repo

We have learned how to push a new bookmark to a remote for the first time. We could do that for every single commit we create and want to push to the remote. However, that would lead to a lot of unnecessary bookmarks lying around. A real mess!

Thankfully, there's a better way. Instead of creating a new bookmark every time, we can move an existing bookmark so it points to another commit.

To try it out, we first need to create a new commit. You can just copy these commands:

printf "\nThis is a toy repository for learning Jujutsu.\n" >> README.md

jj commit -m "Add project description to readme"

The above command uses a neat trick.

If you already have a short description in mind, you can pass it directly to jj commit with the -m flag (short for --message).

This can be faster than opening a separate text editor.

jj log shows us a new commit on top of the one we pushed to the remote:

@ zzywylnt alice@local 2025-07-22 20:36:38 48708b9f │ (empty) (no description set) ○ kxqyrwux alice@local 2025-07-22 20:36:38 6ca38e90 │ Add project description to readme ◆ mkmqlnox alice@local 2025-07-22 20:25:40 main 7939d4cf │ Add readme with project title ~

Now we can send this new commit to the remote by first pointing the bookmark at it and then pushing the bookmark again. Let's start by moving the bookmark:

jj bookmark move main --to @-

We could've told Jujutsu where to move the bookmark using the change ID, i.e. --to kxqyrwux.

Alternatively, we can use @-, which is a neat way to refer to the parent of the working copy commit.

There are many such clever ways to refer to commits, but that's a topic for later.

For now, just remember @-, because that's by far the most useful one.

Let's see what jj log has to say:

@ zzywylnt alice@local 2025-07-22 20:36:38 48708b9f │ (empty) (no description set) ○ kxqyrwux alice@local 2025-07-22 20:36:38 main* 6ca38e90 │ Add project description to readme ◆ mkmqlnox alice@local 2025-07-22 20:25:40 main@origin 7939d4cf │ Add readme with project title ~

The important thing to notice here is that Jujutsu shows us the discrepancy between the local bookmark main and its remote counterpart.

main* is the local bookmark and the star next to the name means it's out-of-sync with the remote.

main@origin is the location of the bookmark on the remote.

We can fix the situation by pushing the bookmark again:

jj git push

This time, we didn't specify --bookmark main explicitly.

If you omit the --bookmark flag on the push command, Jujutsu tries to be smart about which bookmarks you actually want to push.

That usually works quite well.

If you think it didn't work, just try again with the --bookmark flag.

You might be wondering:

Since the remote requires a bookmark to receive commits and the main bookmark is not pointing to the first commit anymore... is that commit now lost or deleted?

Luckily it is not.

Commits store a reference to their parent commit, which is why Jujutsu knows the order in which to draw the commits in the output of jj log.

These references form a chain that protects all ancestors of a bookmarked commit from being lost.

Cloning a remote

Reset your progress

Reset your progress

To reset your progress to the start of this chapter, run the following command:

curl https://jj-for-everyone.github.io/reset.sh | bash -s clone

cd ~/jj-tutorial/repo

At the beginning of the tutorial, we started our journey by initializing a completely new project using jj git init.

We then added a remote later, as a backup solution.

In reality, it's often the other way around:

You need to work on a repository that already exists.

Let's simulate that situation by deleting our main repository:

cd ~

rm -rf ~/jj-tutorial/repo

Now, we only have the remote repository left. How can we get a "local" copy of it so we can continue working? The jargon for getting a copy of a repo is to clone it. The relevant Jujutsu command is named accordingly:

jj git clone ~/jj-tutorial/remote ~/jj-tutorial/repo

The last two arguments are (1) the source from which to clone and (2) the destination - where to store the cloned repo.

When you clone from a remote, you're automatically connected to it with the default name origin.

For the tutorial, we also need to recreate our repo-specific authorship configuration:

cd ~/jj-tutorial/repo

jj config set --repo user.name "Alice"

jj config set --repo user.email "alice@local"

jj metaedit --update-author

Let's run jj log in our fresh clone to see if everything was restored successfully:

@ upopmymm alice@local 2025-09-06 20:42:45 25716c6f │ (empty) (no description set) ◆ ytwonzvp alice@local 2025-09-06 20:42:20 main 0a518bdd │ Add project description to readme ~

The most recent commit we made is visible, but its ancestors are hidden.

In their place is a tilde ~ symbol.

Jujutsu uses some rule to determine which commits are probably not interesting to you.

These commits are hidden by default in the output of jj log.

We can tell Jujutsu to show us all commits with jj log --revisions 'all()':

@ upopmymm alice@local 2025-09-06 20:42:45 25716c6f │ (empty) (no description set) ◆ ytwonzvp alice@local 2025-09-06 20:42:20 main 0a518bdd │ Add project description to readme ◆ psnzzpwy alice@local 2025-09-06 20:41:56 02181db9 │ Add readme with project title ◆ zzzzzzzz root() 00000000

Both of our commits are here, so our repository was successfully restored from the remote.

You made it! At this point, you have all the skills needed for simple solo projects with proper backup. If you're planning to use GitHub, the next chapter is an optional one with tips for that.

Let's summarize the workflow again:

- make changes

- create a new commit

- move the bookmark

- push to the remote

Ideally, you can take a little break now and practice what you've learned. Once you feel comfortable with the above, come back quickly for level 2. We're just scratching the surface.

If you need to collaborate with other people, level 2 is just as essential as this one. I encourage you keep going right away!

Using GitHub (optional)

As promised, here are a few tips about using GitHub. If you are not interested in this, feel free to skip to the next chapter, it won't become relevant later.

I want to mention that GitHub is not the only provider of Git-hosting services, but certainly the most popular one. Unfortunately, it is proprietary. Proprietary software denies you the freedom to read, modify and share its source code. Here is a list of open-source Git-hosting software and service providers who use them. If your digital freedom is important to you, consider using one of these alternatives for hosting your repositories.

Authenticating with an SSH key

Jujutsu needs to authenticate as your GitHub user in order to send and receive commits on your behalf. It's possible to do that with username and password, but it's very tedious and I don't recommend it at all. If making backup is tedious, you will do it less often. Fewer backups means more risk of losing your work! So let's make the authentication as seamless as possible.

The best authentication method is to use an SSH key. It's more convenient and safer than a password. GitHub has great documentation about how to set that up, so please follow the instructions here:

You can verify the setup with the following command:

ssh -T git@github.com

The expected output is:

Hi user! You've successfully authenticated, but GitHub does not provide shell access.

Creating a new repository on GitHub

Skip ahead if you intend to use an already existing repo.

To create a new repository on GitHub, click here and fill out the form. All you need to do is choose an owner (probably your username) and a repo name. Also check that the visibility matches what you want (can be changed later).

If you already have a local repository with content that you want to push to this new remote, make sure to not initialize the repo with any content.

That means, no template, no README, no .gitignore and no license.

Finally, click on "Create repository".

Cloning an existing repo

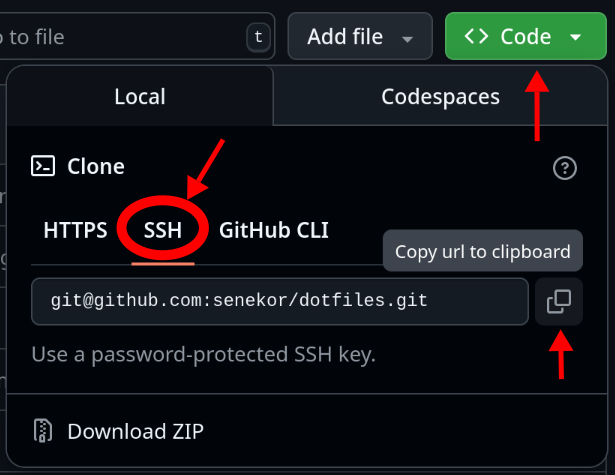

Navigate to the page of the existing repo in the browser. Cick on the green button that says "Code". Select SSH in the drop-down (assuming you have set up an SSH key as explained above). Copy the URL that's displayed.

Finally, paste the URL into Jujutsu's clone command:

jj git clone <COPIED_URL>

Level 2

This level will provide you with the minimum skills to start collaborating with others. If you're a student working on a group project or a professional software engineer, you absolutely need to know this.

Here's the cheat sheet for level 2. You may also want to revise the level 1 cheat sheet.

Fetch new commits from your peers

jj git fetch

Merge your branched-off changes with the main bookmark

jj new main @-

Push your latest commit to a new bookmark

jj git push --change @-

Branching history

Reset your progress

Reset your progress

To reset your progress to the start of this chapter, run the following command:

curl https://jj-for-everyone.github.io/reset.sh | bash -s branch

cd ~/jj-tutorial/repo

Before now, we only covered situations where you are working on a project on your own. What if several people want to collaborate on the project? Let's simulate such a scenario and see what happens. We'll do so in the same repository we used in the previous level:

cd ~/jj-tutorial/repo

Alice and Bob are working on a group project for a computer science class. Their task is to write the classic "Hello, world!" program in Python. Alice and Bob decide to split up the work as such:

- Alice will write the Python program.

- Bob will add documentation to the README.

Let's start with Alice. Here's the Python program she comes up with:

print("Hello, world!")

That'll do the job just fine.

She adds it to the file hello.py:

echo 'print("Hello, world!")' > hello.py

Happy with her changes, Alice creates a new commit:

jj commit -m "Add Python script for greeting the world

Printing the text \"Hello, world!\" is a classic exercise in introductory

programming courses. It's easy to complete in basically any language and

makes students feel accomplished and curious for more at the same time."

Here's how the repository should look at this point:

@ svplvpro alice@local 2025-07-22 21:17:41 4db2d0d0 │ (empty) (no description set) ○ zzywylnt alice@local 2025-07-22 21:17:31 f8e44920 │ Add Python script for greeting the world ◆ kxqyrwux alice@local 2025-07-22 21:14:46 main ffdf52d0 │ Add project description to readme ~

Next, we simulate Bob's work. He's working on a different computer than Alice, with a different copy of the repository. Since Bob is working at the same time as her, he doesn't have the commit made by Alice yet. We can simulate that by creating a third repository, which has the same remote as our primary one:

jj git clone ~/jj-tutorial/remote ~/jj-tutorial/repo-bob

Let's go into that repo, configure our author information for the role-play and make sure the log looks the same way as when Alice started her work:

cd ~/jj-tutorial/repo-bob

jj config set --repo user.name Bob

jj config set --repo user.email bob@local

jj metaedit --update-author

jj log

@ quolxwkk bob@local 2025-07-22 21:19:11 3ffac111 │ (empty) (no description set) ◆ kxqyrwux alice@local 2025-07-22 21:14:46 main ffdf52d0 │ Add project description to readme ~

That looks great. So now, Bob is going to do his part the same way Alice did:

echo "# jj-tutorial

The file hello.py contains a script that greets the world.

It can be executed with the command 'python hello.py'.

Programming is fun!" > README.md

jj commit -m "Document hello.py in README.md

The file hello.py doesn't exist yet, because Alice is working on that.

Once our changes are combined, this documentation will be accurate."

Let's say that Bob was a little faster than Alice, because he was only doing the documentation. Alice was doing actual software engineering, which took a little more time. Therefore, Bob gets to update the main bookmark first:

jj bookmark move main --to @-

jj git push

A little later, Alice is also done.

Now she attempts to update the main bookmark, which will fail:

cd ~/jj-tutorial/repo

jj bookmark move main --to @-

jj git push

Changes to push to origin: Move forward bookmark main from cd5f3fff9c7b to e90b597ed78e Error: Failed to push some bookmarks Hint: The following references unexpectedly moved on the remote: refs/heads/main (reason: stale info) Hint: Try fetching from the remote, then make the bookmark point to where ↪ you want it to be, and push again.

Alice is about to panic, so she opens social media and scrolls a little until she finds a cat video. She finds one where a cat is snuggling with a bunch of baby ducks! Super cute. Now that her nerves are calmed, she turns her attention back to the terminal and actually reads the error message. She is relieved to find that it actually contains useful information about what went wrong and how to fix it. Following the hint, she first fetches from the remote:

jj git fetch

fetch is a new command, it's basically the opposite of push.

While push sends bookmarks and commits from the local repository to the remote, fetch downloads bookmarks and commits that someone else (like Bob) may have pushed from another computer.

Here's the resulting jj log:

@ svplvpro alice@local 2025-07-22 21:17:41 4db2d0d0 │ (empty) (no description set) ○ zzywylnt alice@local 2025-07-22 21:17:31 main?? main@git f8e44920 │ Add Python script for greeting the world │ ◆ quolxwkk bob@local 2025-07-22 21:22:22 main?? main@origin 8d538390 ├─╯ Document hello.py in README.md ◆ kxqyrwux alice@local 2025-07-22 21:14:46 ffdf52d0 │ Add project description to readme ~

Oh! That's something we haven't seen before. Our version history is split into two branches. This is not unusual and lies at the core of how Jujutsu enables people to work independently from one another. But we don't know how to deal with this situation yet.

If Jujutsu allowed Alice to push the main bookmark without knowing about Bob's update, his work would accidentally get deleted.

Remember: The remote only considers commits worth keeping around if they are reachable from a bookmark.

But if the main bookmark points to Alice's commit, Bob's commit is not reachable anymore, because it is not an ancestor of Alice's commit.

Notice that the main bookmark appears twice in the log, both times with question marks ??.

This means Jujutsu isn't sure where the bookmark should point to.

Alice moved it to her commit, while it was moved to Bob's commit on the remote.

Once Alice has decided where it should actually point, she can tell Jujutsu by explicitly moving it there.

The terms "bookmark" and "branch" are often used in very similar situations, which can be confusing. Let's define the difference very precisely and prepare ourselves to recognize potential sources of confusion.

A bookmark is just a named label that's attached to, or points to, a single commit. That's it.